I am a horror writer.

The last of a dying breed.

Actually, perhaps I’m already dead and just don’t know it yet.

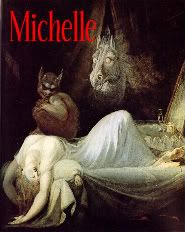

I didn’t intend to be a horror writer, and if I’d had any commercial sense at all, I would have delved into paranormal romance, chick lit, suspense, mystery, and fantasy. All of which I write, by the way, often in the same book, but the word “Horror” is stamped on the spine. At the fork in the publishing road, as Robert Frost wrote, I took the one less traveled by, and all the difference has been made.

Showing up early for a recent signing, I had time to browse the store a little bit, checking out the competition, wading past the pirate and Da Vinci material to reach the fiction section. I looked for the titles of my friends, who are also horror writers. Miraculously, practically overnight, the spines of their books had been changed to read simply “Fiction.”

I was all alone, and that was scarier than any ghost or monster I had ever penned. I’m not vain enough to believe I had suddenly become the standard bearer for a fading genre. No, what had changed was the publishing industry perception of the label. The publishers’ sales teams believe horror doesn’t sell, so they convey this lack of enthusiasm to the bookstores. The bookstore owners don’t order it, and because readers don’t see it on the shelves, they believe horror must no longer be readable.

Horror is many things to many people. Author and anthologist Doug Winter once announced “Horror is an emotion, not a genre.” He said this a decade ago, long after the end of the 1980’s horror boom, when evil dolls, sharp-toothed critters, and decrepit manors adorned dozens of books each month. The genre born with “The Odyssey” and “Grendel,” passed up through “MacBeth” and on to “Frankenstein” and “Dracula,” reached its zenith with “Rosemary’s Baby,” “The Exorcist,” and an extraordinary average guy named Stephen King. Horror was selling like hotcakes, and even when the good times faded, largely due to an avalanche of crappy hackwork, a couple of publishers still maintained horror lines, turning out one or two horror titles a month.

Until a few years ago, when I alone survived, though I was already half dead because my mass-market shelf life was comparable to that of cottage cheese.

Within the horror community, the discussion over the “death of horror” was broken into two separate issues—a belief that “horror elements,” the ghosts, vampires, serial killers, and essential human fears that are the root of good storytelling have expanded and are touching more genres and writers and readers than ever.

Romantic suspense writer Iris Johansen wrote a novel that features a woman who wants to turn people into zombies. Kay Hooper’s bestselling series features psychic special agents. “The Lovely Bones” and “Beloved” are built on supernatural frameworks. One can hardly turn around without being poked by a stake-wielding, scantily-clad woman on a book cover who is drooling over a well-oiled Fabio with fangs. So horror, the emotional effect, seems to be quite popular.

And then there’s “horror,” the label, the market anathema.

The brand that’s no longer in stores, despite the plethora of ghosts, goblins, witches, and vampires that still crowd the shelves. The brand that rarely merits its own bookstore section, and when it does, those shelves contain little more than King, Dean Koontz, and Anne Rice, whose books are all labeled “Fiction.”

I watched people’s faces at my signing. Some saw the “horror” label, set the book down, patted the spooky scarecrow cover, grimaced, and made a brisk escape. A couple muttered, “I don’t read that kind of stuff,” or, “I don’t read horror, I only read King and Koontz.”

“But it’s not horror,” I wanted to say, not sure whether this constituted smart marketing or just plain lying. “This book is about the relationship between a mother and her daughter—it’s chick lit! It draws on Appalachian culture and religion. It’s a mystery, a paranormal romance, a psychological thriller—whatever category you want it to be!”

Who cares about the man-eating goats? What about the long sex scene where the new wife is possessed by the ghost of the dead wife? Those are sprigs of parsley, added for color and not taste. Those who take the time to talk to me about the story usually end up buying a copy, even people who profess a dislike for the genre. Once they get past that “H-word,” they see the story may serve up more than just the rehashed tropes and murder-by-numbers plots that plague too many modern horror movies.

My horror peers were a step ahead of me. They quit calling their books “horror novels.” Now their agents pitch them as “supernatural thrillers.” Same books, different words, higher advances, more marketing, a collective sigh of relief from the sales departments. At last they have books they can sell without embarrassment, as if horror were the literary equivalent of naughty pictures.

And then the indie revolution happened, and horror is back out of the closet, breaking the invisible chains that sought to keep it from the light.

I was the last horror writer in America, but only for a dark moment in literary history. Now we are everywhere, shambling, clawing, growling our way back into the hearts of readers, you who thirst like a coffined vampire or hunger like the last of the living dead.

Eight of my writing peers are happy to march in the ranks, and their contributions are shared here in our communal anthology project. Vampires, ghouls, zombies, serial killers, and other creepy creatures of the night infest these pages, proud to disturb your sleep or stir your fevered imagination.

Horror is back, but it never really left, because horror doesn’t die. And it doesn’t care. Horror just is.

To be entered to win a $10 gift card from your choice of Amazon or B&N, 'like' American Horror

on Amazon or B&N and share this post on Twitter or Facebook. Leave a comment telling me what you did and leave your share link(s) as well. Be sure to leave your contact info (valid email address). American Horror

is available in eBook formats on Amazon, B&N, and Smashwords.